The life and times of Clifford B. Harmon

In a talk at the Croton Free Library, village historian Marc Cheshire painted a colorful portrait of the real estate developer who left an indelible mark on our village.

Croton history buffs were out in force again Thursday evening, as village historian Marc Cheshire prepared to give his last talk of the year. Unfortunately, the first half hour was taken up with solving some technical problems with the projection system in the Croton Free Library’s Ottinger Room. But that did not phase the audience, which picked up seamlessly from Marc’s last talk, about the stone houses of Croton, peppering him with still more questions as if the Q&A session from that presentation had never ended.

(In a very relevant digression, Marc also informed the crowd—at least those who did not already know, since long-time Crotonites are fiercely proud of their knowledge of village history—that the Ottinger Room had been named after Egon Ottinger, a man who lived very modestly in a stone cottage on the Croton River. When Ottinger died, he left a $20 million estate behind from his career in the shipping business, which included doing business with Aristotle Onassis. A nice chunk of that money went to build the meeting room that bears his name.)

Finally, with Hoorahs! all around, Marc’s first slide flashed on the screen, and his discourse on “Harmon, the New City” began.

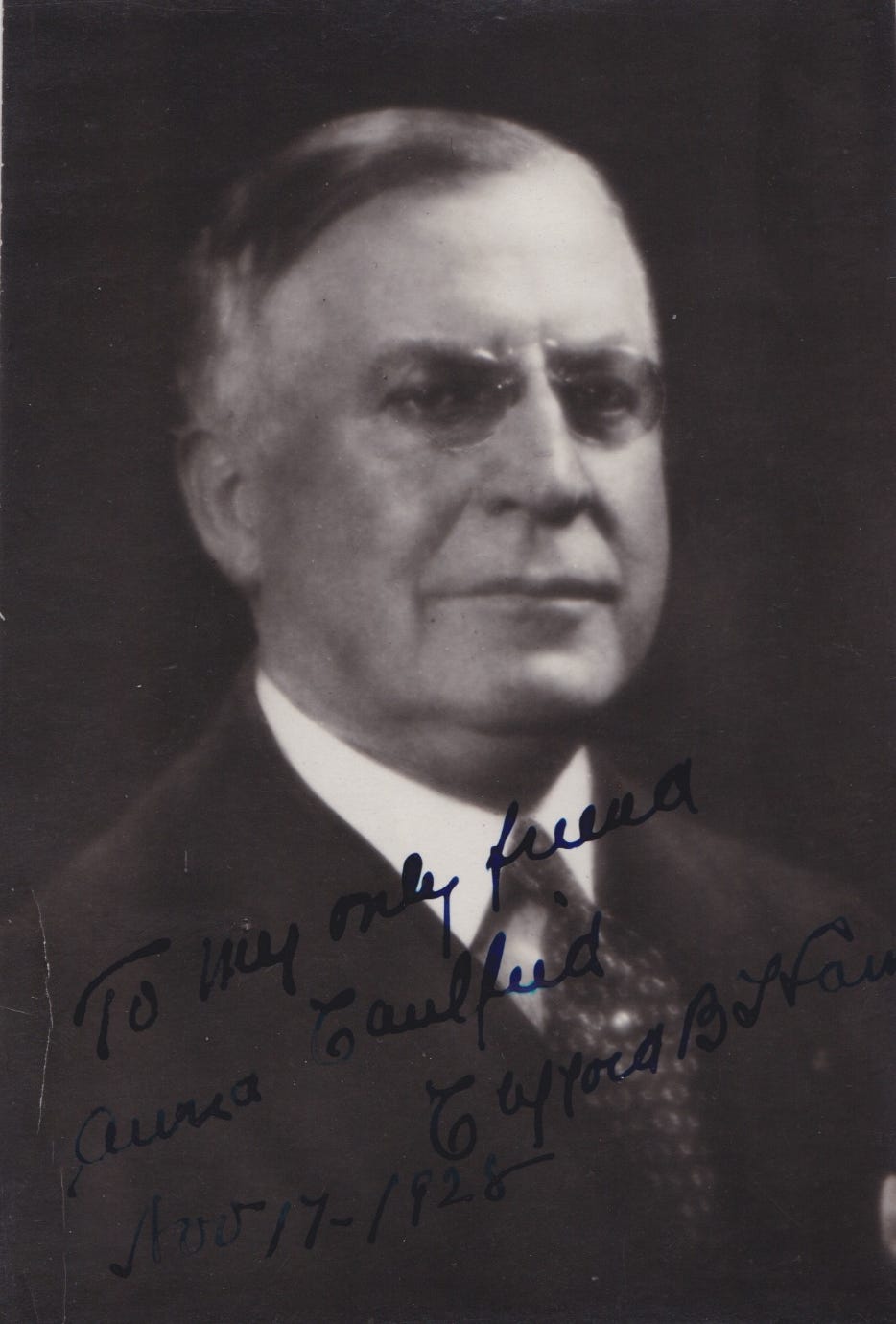

Clifford B. Harmon grew up in Ohio, along with his older brother William. Their father, William R. Harmon, had fought in the Civil War and later was an officer in the Buffalo Soldiers, the mostly African-American regiment. (The younger William later became a patron of African-American art.)

In his younger days, Clifford was known as a dashing aviator, hot air balloon enthusiast, and wealthy playboy, Marc told the gathering. Among his exploits was a historic repeated circular flight over Long Island Sound in 1910, remaining aloft for an hour and five minutes and setting a new amateur record for time in the air. (He later established The Harmon Trophy for international aviation achievement, which is now housed at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.)

“Clifford loved the limelight,” Marc said. But while he was becoming famous for his exploits in the air, he left his biggest mark on the ground, especially here in Croton. In the late 1880s, Clifford, his brother William, and their uncle, Charles Wood, invested $1000 each to form the Wood, Harmon company. They eventually opened branches in 18 cities, and in 1898 opened an office in Brooklyn. Clifford had long had his eye on Westchester County, and by 1907 had formed his own development company.

A new rail yard had opened south of Croton, so Clifford Harmon bought the old Van Cortlandt family farm and launched an intense campaign to develop the land.

By the early 1900s, Croton already had a reputation as an artist’s colony and retreat. So it wasn’t hard for Harmon to attract celebrities to buy property in the area. Among them was Lillian Nordica, the opera singer, who bought 20 acres and planned to open an opera house and school in the town. Sadly, she died in 1914 before she could realize those plans. Her name, of course, is now attached to a picturesque street along the Croton River.

The actress and playwright Margaret Mayo, whose name now graces a landing on the Croton River on Nordica Drive, also came to live in Croton, in a house by the Duck Pond. Mayo founded a playhouse at the corner of Truesdale and Nordica; the building is still there, tucked away a bit out of sight.

Harmon’s sales office was at the corner of what is today Riverside and Benedict; the building still stands, now housing a nail salon.

The Truesdale-Nordica enclave also became the site of two competing Japanese “tea houses,” the Nikko and the Mikado. During Prohibition, Marc divulged, both served as speakeasies. Among those who tinkled the ivories at the Mikado was a very young Oscar Levant, whom older members of the audience would immediately recognize as the somewhat notorious piano player and comedian.

In an autobiography, “The Memoirs of an Amnesiac,” Levant described his experiences. Marc quoted briefly from this passage, but it is worth reproducing at greater length:

"During my second year in New York I played the piano in a Japanese roadhouse in the town of Harmon-on-the-Hudson, where I shared sleeping quarters with twenty or thirty Japanese waiters in the cellar. . . .

A three-piece orchestra played on weekends but during the week there was just the piano and violin. We alternated between classical and popular music. The place was called Mikado Inn. The rival restaurant . . . was the Nikko Inn. Japanese restaurants were comparatively scarce, so it was ironic that the leading proponents of Japanese cuisine should have been within such a short distance of each other. Consequently, the rivalry was keen.

The upright piano on which I played had a horizontal string across it, on which hung a one-dollar bill—a not too subtle hint for tips, which were mostly forthcoming as the evening progressed and the clientele grew boisterous and drunk. The most popular request was that great American spiritual "Show Me the Way to Go Home." Almost as popular were "Charlie My Boy," and "Yes, We Have No Bananas." For dinner we played concert music.

The proprietor, a rotund, jovial Japanese whom we addressed as Admiral Moto, was completely dominated by his forbidding Irish wife, a tall, dictatorial and quite respectable woman. Every Saturday night Admiral Moto would get loaded . . . There was great activity in the vast kitchen where the chef was a twenty-year-old Italian boy from nearby Croton. He had achieved his Oriental culinary skill under the tutelage of his predecessor, a Japanese chef who had left after a fight with Admiral Moto. This was an interesting anomaly: an Italian chef running a kitchen which served only sukiyaki.”

While all this was going on, Croton and Harmon were separate villages. But since 1907 there had been discussion of merging them. Instead, in June 1930, Croton annexed Harmon and the village took on its current name of Croton-on-Hudson.

In the latter part of his talk, Marc told the audience that he was working on a project researching the names of Croton streets, and gave some examples. It turns out that a number of them were named people and places in Harmon’s life, including his wife’s side of the family—especially those of his father-in-law Commodore Elias Cornelius Benedict. (In 1904, his second marriage, Harmon had married Louise Adele Benedict.)

Thus were named Benedict Boulevard; Oneida Avenue (after a luxury yacht owned by the Commodore); Cleveland Drive (after Benedict’s friend, President Grover Cleveland, who had a secret cancer operation on the yacht); Truesdale Drive (after a friend and business associate of the Commodore); Hastings Avenue (after Harmon’s brother-in-law, architect Thomas Hastings), and so forth.

With all this family naming, one would think that Harmon and his wife would have lived a long life together. But in 1916, according to Wikipedia, Harmon left Louise after a big argument with her father, was cut out of his will, and finally divorced his wife in 1925.

In the meantime, he went off to serve in World War I, moved to Paris, died in Cannes in 1945, and is now buried in the Rhone American Cemetery and Memorial on France’s Côte d'Azur.

Harmon’s death, ironically, corresponded with the real postwar explosion of development in the Croton-on-Hudson we know today, which, despite all of Clifford’s efforts, did not really take off until after World War II.

And so came the end of the man who made such a huge mark on our village. At the end of his talk, Marc told the crowd that he was probably going to take a break from giving history talks in the coming year (do we really believe that?) and invite some guest speakers to give their own presentations (that would be good, of course.)

Whatever happens, we will be there to cover it.