Chronicle profile: Croton-on-Hudson's village historian, Marc Cheshire

Croton has a rich history from many time periods, and since 1919, able historians to keep track of it all.

[Note: This article, like all profiles of local people in The Croton Chronicle, is free to all readers.]

It’s nearly 7 pm on a Thursday evening in the Ottinger Room of the Croton Free Library. Village historian Marc Cheshire is looking more pleased as each moment passes. That’s because people are still flocking in for his talk on Croton’s stone houses, a collection of architectural gems built along Old Post Road North in the early 1900s by “socialite” Elisabeth Farrington Stevenson and her son, Harvey.

Soon all the folding chairs are filled. Some visitors sneak into the library’s reading room to grab wooden chairs, before they are stopped by library staff. So it’s standing room only as Cheshire begins his talk. He takes the audience house by house, using old and new photos and painting vivid portraits not only of the Stevensons but the illustrious artists and writers who once lived in the houses. There is a flutter of excitement when Cheshire tells the crowd that one of them is for sale (price tag around $2 million.)

Since 2018, when Croton Mayor Brian Pugh appointed Cheshire as Croton’s 10th village historian, he has been taking villagers for walks—literally and figuratively—through the history of our village, which was first incorporated in 1898 (and whose 125th anniversary we are still celebrating.) On many weekends, Cheshire, often accompanied by Croton Point Park naturalist John Phillips, leads tours of Croton Point, Croton’s Upper Village, or other historical spots.

Cheshire doesn’t do this for the money. The position of village historian is purely a volunteer post; but fortunately, there are numerous other volunteers who help to keep the history of Croton alive. Many are affiliated with the Croton Historical Society and Croton Friends of History. It’s a good thing, because otherwise Croton would be in violation of one of New York state’s most solemn laws: The Historian Law, signed by governor Al Smith in 1919, one of the first in the country to require each village, town, and city in the state to have its own official historian.

It’s no surprise that the law-abiding citizens of Croton have followed this to the letter, although Cheshire says that not every municipality has done so. So when the police department was allotted more space in Croton’s municipal building and the history society had to move, it got even more space in the building’s basement. While that decision was not applauded by everyone, Cheshire says he is happy with the deal and especially with the greatly increased space for storing archives and for volunteers to work.

“A lot of towns don’t support their historical societies,” Cheshire says. “Croton really does.”

Like so many local historians, Cheshire is an amateur practitioner of the discipline, albeit as passionate as any professional, if not more so. But when he was younger, he dallied for a while with the idea of becoming a journalist like his parents, writing “first drafts of history” as reporters often see themselves doing.

Cheshire was born in Washington, DC and grew up in northern Virginia. His father, Herbert Cheshire, worked for United Press International, Business Week, and eventually McGraw-Hill World News. His mother, Maxine Cheshire, was a legendary reporter and columnist for the Washington Post, who turned the paper’s “For and About Women” page into a hotbed of scoops about Jacqueline Kennedy and other notables and newsmakers.

When Maxine died at age 90 in 2021, her obituary in the Post quoted one editor as saying she had “the guts of a cat burglar.” (The same obit also quoted Maxine as telling the first editor she worked for, at Kentucky’s Harlan Daily Enterprise, “I know everything that goes on in this town, and if you give me a job so will you”—an opening line many cub reporters might have wished they used in their first job interviews.)

Marc, the oldest of the couple’s children, had lots of exposure to journalism—he still remembers the clacking of the teletype machine when his father would take him to work with him—but gravitated towards art and design as high school student. His parents insisted he go to college, however, and so he ended up at Brown University in Rhode Island. While there, he and a college roommate landed a big scoop in a 1978 issue of the short-lived New Times magazine: They broke the story that a former president of Brown, Barnaby Keeney, had worked covertly for the CIA.

After graduating from Brown, Cheshire began a career in book publishing, and ended up as the director of childrens’ books for Henry Holt. He later ran the English and Spanish language imprints of the Swiss publisher NorthSouth Books, and about 20 or so years ago went freelance.

In 1994, Cheshire moved to Croton, buying a house on Larkin Place, a street chocked full of history (although there is still controversy over whether the so-called Larkin Place Skeleton belonged to a Native American or not, as had been claimed.)

“Croton wasn’t very expensive at that time, and of course it was beautiful,” Cheshire says about his choice of new home. It turned out one of his neighbors was the late Joyce Finnerty, who became village historian in 1999. When Finnerty told him that his house was made of stone left over from the construction of the New Croton Dam, and also that the Larkin Place Skeleton had been found at the end of his driveway, Cheshire was hooked.

Cheshire began researching such landmarks as the Underhill Wine Cellars at Croton Point Park, the Old and New Croton dams, and of course the houses of the village. He also became “obsessed” with Clifford Harmon, the real estate developer who put such an important mark on Croton-on-Hudson in the early 20th century (Cheshire hopes to fill the library’s Ottinger Room once again on December 14, when he gives a talk about Harmon.)

Two more historians would come and go after Finnerty, and finally, in 2018, it was Cheshire’s turn. (The Fall 2019 issue of the Croton Historical Society’s newsletter, The Croton Historian, features biographies of all ten Croton historians, compiled by local Croton celebrity Cornelia Cotton.)

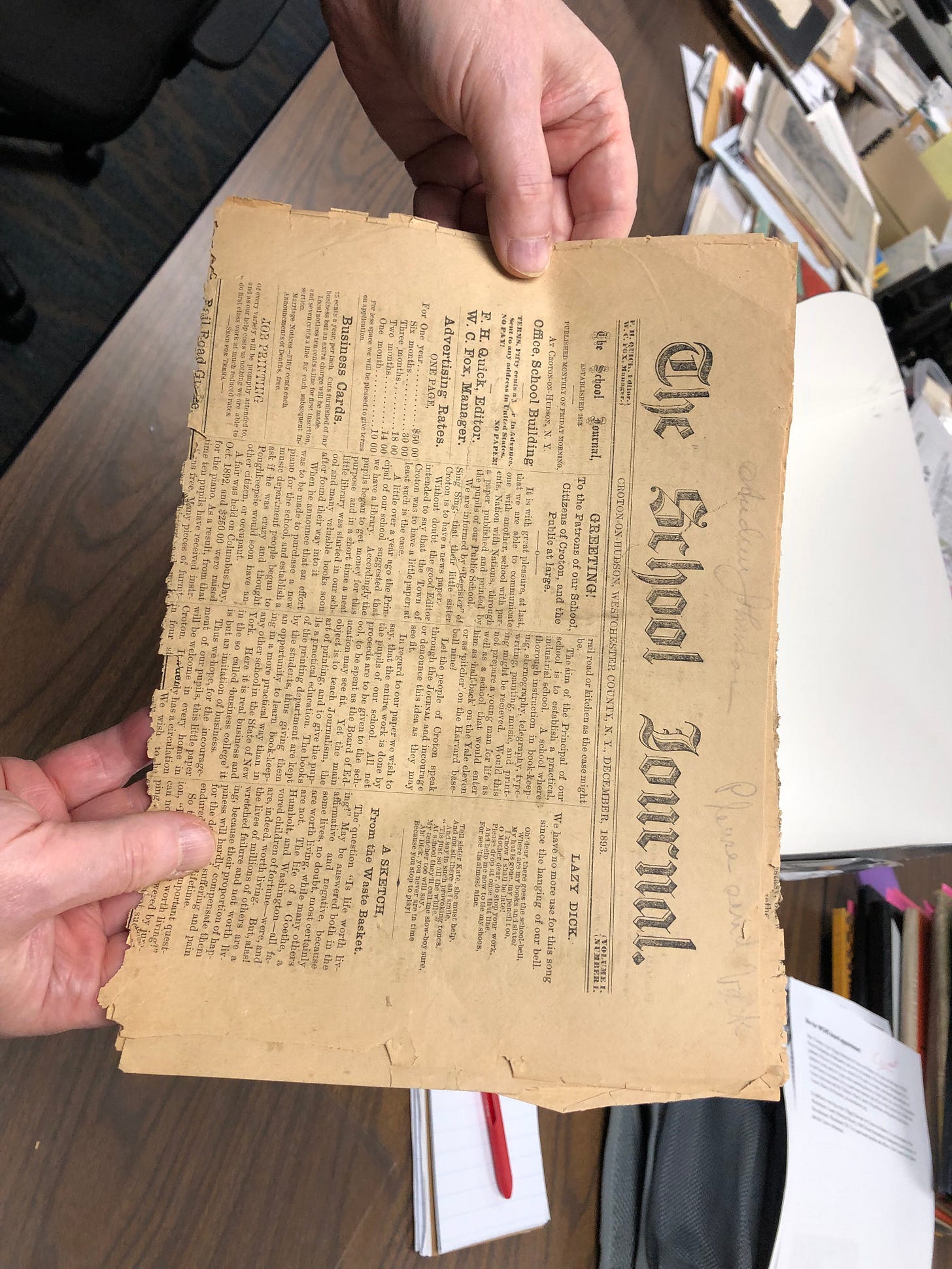

And with the 125th anniversary events winding down, Cheshire plans to continue with some of his own current research projects, which include the history of the press in the village and local region, as well as the origins of street and place names in Croton.

A historic village like Croton deserves a dedicated historian. With Marc Cheshire, we can be sure our local history is in good hands.

Very thankful our Village has such a dedicated historian.