Of Fish and the River: Chris Letts is still teaching the children well.

A Chronicle profile. When the shad ran in the Hudson, Letts was there, fishing and teaching. He's been on the river much of his life.

It’s a little after noon at Croton Point Park, and a big yellow school bus is just pulling into the parking lot. Chris Letts is already down at Mother’s Lap Beach, and he is ready for them. The wind is kicking up, and the mighty Hudson is already getting choppy, but that’s no matter. In a few minutes, about two dozen second graders from Coman Hills School in Armonk, along with their teachers and a couple of parents, begin marching across the green grass.

Chris has been teaching kids about the Hudson River and the fish that swim in it for more than 40 years. This morning he has two helpers: John Phillips, Croton Point Park’s naturalist, and Julia Snook, curator of the Lenoir Preserve in Yonkers. Julia has her waders on, as she has been chosen to walk into the river for Chris’s demonstration of river seining. With John’s help, and a brief assist from one of the parents, the team stretches the seine across a section of Mother’s Lap Beach.

Never mind asking how many fish they caught in the seine. There are not as many fish in the Hudson as there once were, and the river has silted up along Mother’s Lap Beach. The kids don’t seem to mind. Then they all troop back up on the grass while Chris regales them with various facts about fish and the river. The kids seem happy, and that’s all that counts.

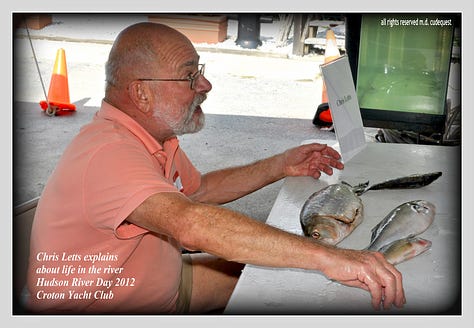

If you visited Hudson River Day at the Croton Yacht Club last September, you may have seen Chris there as well. On that occasion he was staffing the Fish Touching Table. Spread out on the table were various kinds of fish, already gutted, and ready to be touched by anyone who wanted to and was not too squeamish.

“People are fascinated by fish,” Letts says. “They just don’t know how to approach them. The kids just love it.”

Fish have been part of Letts’s life from a very early age. He was born in Detroit in August 1941, which makes him 83 years old today. His mother came from a famous farming family, and his father was an organic gardener. Letts grew up in the Detroit suburbs, where he learned to hunt, fish, and trap animals.

“From the time I was a little kid I had to be outside,” he says

Even at the supermarket he could not stay away from the fish. That made it easy for his parents to find him when he wandered off. They would just make their way to the fish counter where young Chris would be examining what was on offer.

By age 15 he had two ideas of what he wanted to do in his life. One was to be a forest ranger, and the other to be a commercial fisherman. He would eventually get to do variations of both. His first big break was in high school, when he got a job as a staff member at a summer camp and worked as the camp naturalist.

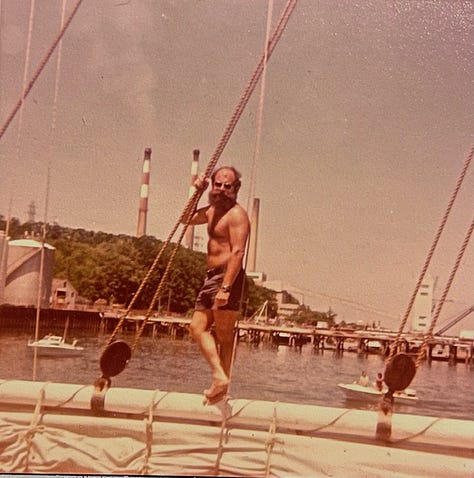

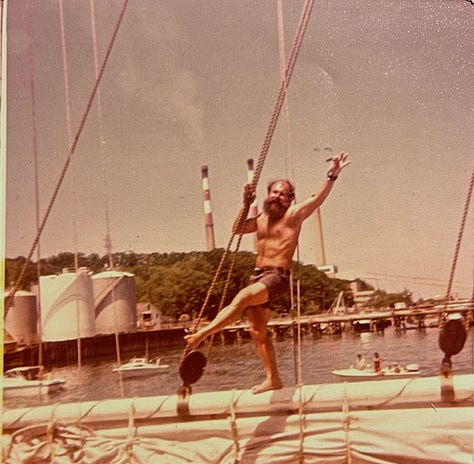

As an adult, Letts landed a number of jobs, some short and some longer, all involving the outdoors in one way or another. He was a ranger at Isle Royal National Park in Lake Superior, Michigan; spent three years in the early 1970s working at Tenafly Nature Preserve in New Jersey; and then from 1975 to 1978 worked as an educator on the Sloop Clearwater.

Letts would commute between these jobs on the East Coast and Michigan, not quite sure where he wanted to end up. He got his first grant as a river educator in 1980, and in 1981 the Hudson River Foundation offered him a staff job to develop education programs up and down the Hudson, mostly between Yonkers and Cold Spring.

Soon schoolchildren and their teachers were coming from all over Westchester County and beyond to learn from Letts. A Chronicle reader, who asked to remain anonymous, remembers school trips when he was in elementary school:

“We always looked forward to our field trips to Croton Point Park. The common theme during these trips was getting to experience Chris Letts seining the river and seeing all of the cool fish and other creatures he would bring up. Not only was it fun and helped us appreciate wildlife, Chris himself was always so joyful and wonderful in dealing with us all. The trips were 30 years ago, but I can still place myself at the river watching the net come up, Chris with his glasses and big smile. I’ve been fortunate to see Chris around town every so often since and he still has the same friendly demeanor and positive attitude. I think of him as holding a wealth of river knowledge and being a treasure of a person.”

Letts kept that job for a quarter of a century, until, he says, a member of the Hudson River Foundation board visited his program and later told colleagues that they didn’t need a river educator, the students could just use an app on their smart phones. Soon after he was cut loose.

But during those years with the foundation, students from all around would come to learn from him. And adults. One of the biggest and most popular activities were shad festivals and shad bakes, which readers who have been around for a while are sure to remember.

Those not familiar with American shad (Alosa sapidissima), a large species of the herring family, might check out the great writer John McPhee’s book on the subject, “The Founding Fish.” The shad was once the Hudson River’s most important fish, and many fishermen made a fortune catching them. Shad are bony, as are all herring; Indigenous people called them “the porcupine turned inside out.” It took some training to learn how to bone them properly, and Letts became a master of the art.

That made him a valuable part of the shad festivals and shad bakes that, especially during the 1980s, became one of the most popular activities on the Hudson River. Politicians, philanthropists, environmental organizations like Riverkeeper, all got in on the shad bake action.

Chris Letts was right in the middle of it. A 1987 article in the New York Times, “Savoring the Delights of Shad at Festivals Along the Hudson,” captured the mood of this fishing frenzy and the key role Letts played in it all.

“The shad, although primarily an ocean fish, returns to spawn in the rivers where it was spawned. The shad run is fleeting, beginning in the northeast in late April and ending by early June. For the most part, the season has already ended in New York City. North of the city, however, the water turns warm later in [the season] and shad may still be available in some northern areas including Connecticut.

''When the forsythia bushes are in bloom the shad are in the river, but when the lilacs come out it's all over,'' said Christopher Letts, an environmental educator with the Hudson River Foundation, a nonprofit organization that has helped organize many shad festivals along the Hudson.

This spring New York shad festivals have been held in Nyack, Beacon, Garrison, North Tarrytown and Kingston; one was held in Fort Lee, N.J. And at many of them Mr. Letts, wearing his ''Eat More Shad'' T-shirt, has been a familiar figure.”

Letts would help cook the fish at many of these events, wrapping them in bacon, placing them on long wooden planks, and baking over an open fire.

But alas, the good shad times could not last forever. Overfishing and competition from large-mouthed bass and zebra mussels caused shad numbers to plummet. Finally, in 2010, New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation closed commercial and recreational shad fisheries. The DEC has been trying to bring the shad back ever since, but with only limited success.

It was while teaching children about the river that Letts met his wife, Nancy, in the early 1980s. She was teaching at the Post Road School in White Plains, and every year the children would come out to Croton Point Park. Letts says he fell “head over heels” the first time he laid eyes on her, but “it took me three years to get her attention.”

When he did, the couple bought the house on Furnace Dock Road where they live today. Letts is doing fewer programs than he used to, and now spends a lot of time gardening. He grows cherry tomatoes (the Chronicle’s editor can attest to their sweetness), squash, raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries, and flowers that adorn his stretch of the road and give lots of pleasure to neighbors passing by with their dogs.

But fish are still a big part of his life, as can be seen every year at Hudson River Day at the Croton Yacht Club, where Letts and his fish touching table are always a major attraction.

Says Letts: “I never met a fish I didn’t want to touch.”

**********************************************************************************************************

To share this post, or to share The Croton Chronicle, please click on these links.

Interesting piece, Michael! My kids remember going to Chris' demonstrations when they were at the Croton Schools. They were intrigued at seeing him eat raw anchovies that had caught!

Wonderful article for an amazing person!