Lorraine Hansberry Coalition hosts expert Chicago author on housing discrimination.

Natalie Moore, author of “The South Side,” discussed housing discrimination in Chicago and beyond at the Croton Free Library.

Note: This post is free to all readers, but not all our stories are or can be. Please support local journalism by taking out a paid subscription to The Croton Chronicle. Details at the bottom.

Lorraine Hansberry’s most famous play, “A Raisin in the Sun,” was set in South Side Chicago, where Hansberry spent a lot of her youth and where she learned about racism in America first hand. Her father, Carl Hansberry, was a dedicated campaigner against housing discrimination, taking the issue all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court and winning a landmark decision in Hansberry v. Lee.

But while Chicago can claim a big part of Hansberry’s legacy, so do we here in Croton-on-Hudson. In 1961, in the wake of the massive success of “Raisin,” Hansberry moved to Croton and a house off of Quaker Bridge Road. She jokingly called her house “Chitterling Heights,” and when she died of cancer in 1965, she was buried in Croton’s Bethel Cemetery. While alive, she helped organize a major civil rights gathering at Temple Israel, but apparently kept mostly to herself and did not involve herself in village affairs.

While we in Croton are proud of the many famous people who have lived here, some villagers have mixed feelings about Hansberry. She was a lesbian and a political radical, with earlier ties to the Communist Party. It is interesting to ponder what kind of role she might have played in Croton had she not died so young.

Nevertheless, some Crotonites are determined to keep Hansberry’s memory and legacy of activism alive. To that end, in 2021, a group of villagers founded the Lorraine Hansberry Coalition (LHC), which, according to its page on the village Web site, “is dedicated to celebrating the life of acclaimed playwright, author, and activist Lorraine Hansberry and her connection with Croton-on-Hudson.”

Last Saturday, the LHC hosted a visit by Chicago-based Natalie Moore, a journalist, author, and playwright who focuses on segregation and inequality issues. Among other works, she is the author of the award-winning book “The South Side: A Portrait of Chicago and American Segregation.” Before an audience of about 100 people in the Croton Free Library’s Ottinger Room, Moore discussed many of her findings in that study in a panel with LHC co-chair Lynda Jones and Westchester Human Rights Commission executive director Tejash Sanchala, a frequent guest at LHC events.

But before the panel began, LHC co-chair Signe Bergstrom set the stage by providing a short but detail-packed history of the Hansberry family’s involvement in the fight against housing discrimination. Lorraine’s father, Carl Hansberry, was a real estate broker who had moved his family to a white neighborhood in Chicago in the late 1930s, when Lorraine was eight years old. In events that are mirrored in “A Raisin in the Sun,” the family immediately ran into racist oppositions from their neighbors, who relied on the private “restrictive covenants” that effectively reserved certain areas of the city to whites.

The 500 houses in the neighborhood were all covered by restrictive covenants, although they were not always enforced. Thus Carl Hansberry had been able to buy a house from a white policeman, through a third party, who had actually helped to write the restrictive covenant in the first place (Bergstrom explained that the policeman had an “epic falling out” with the neighborhood association over an unrelated issue, and apparently he was seeking some kind of revenge.)

But when the neighbors tried to enforce the covenant against the Hansberry family, Carl assembled a legal team and began to fight. Lower courts upheld the racist rules, but in 1940 the U.S. Supreme Court held against the homeowner’s association on what was partly a legal technicality and partly a 14th Amendment due process question. Not until 1948 did the Supreme Court rule that restrictive covenants could not be enforced by the courts, in the famous Shelley v. Kraemer decision.

As Signe Bergstrom explained, however, even that decision did not prevent restrictive covenants from being agreed to between private parties. Only in 1968, when Congress passed the Fair Housing Act, did both public and private discrimination in housing become illegal across the land.

The panel with Natalie Moore then began. Prompted by questions from Lynda Jones, Moore laid out the historical background for restrictive covenants in Chicago. The so-called Great Migration, which began in the early 20th century and continued for decades, saw some six million African-Americans move out of the South and into other areas of the United States. (This epic movement of people was described in Isabel Wilkerson’s “The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great Migration.”)

For Chicago, Moore said, the arrival of so many Blacks in a short period of time triggered a quick racist reaction. Being white “is an ethnicity in Chicago,” Moore said, and there were soon a number of deadly incidents. In response, in 1922 the city put together a commission on race relations, which produced an 800 page report recommending that housing not be segregated in Chicago.

Instead, Moore related, “the city did the exact opposite.” But instead of enforcing strict segregation, which after all was a southern and not a northern thing, restrictive covenants were entered into by entire city blocks. Chicago pioneered this style of racism, Moore said. “A lot of housing discrimination was workshopped in Chicago.” She added that the language in the covenants varied in how it referred to African-Americans, sometimes using the term “Negro,” sometimes “non-Caucasians,” and sometimes referring to those of “African blood.”

In 2021, Moore teamed up with NPR and other journalists to produce a program entitled “Racial covenants, a relic of the past, are still on the books across the country.” The team discovered that “restrictive covenants are very hard to find,” Moore told the gathering, and are often buried “in the bowels of county records. It took me three hours to find the first one.” Even though they were no long enforceable, these agreements still exist in writing. “The apartment building I was living in was covered by a restrictive covenant,” Moore discovered.

The team did a “public callout” as part of the reporting, including taking out ads in The Chicago Tribune. As Chicagoans uploaded copies of the covenants online, the reporters found that many of them were in suburbs where African-Americans had showed no desire to live. “The message of this [for whites] is, you are safe because no Negroes will be coming here.”

Moore stressed her view that the most accurate way to describe segregation in cities like Chicago is to call it “white segregation,” arguing against assumptions that segregation is the result of Black people wanting to live only in Black neighborhoods. “My father grew up on the South Side,” Moore said, “and he could not go to the nearby white school even though his own school was overcrowded.”

In response to some questions from Tejash Sanchala, Moore pointed out that housing discrimination today is carried out using “race neutral” language, and has adopted new strategies to hide its true intent. For example, recent studies have shown that real estate appraisers sometimes use different standards to appraise the houses of white and Black homeowners, and that tax codes also contain hidden features that are discriminatory in effect if not in intent. Sanchala told the audience that a federal task force is working on such issues at the moment.

At the end of the panel, Lynda Jones asked Moore what she learned about herself and why she wrote “The South Side.”

“Chicago will never live up to its role as a global world class city if it does not address [still existing] segregation,” Moore responded. “You can’t move forward if you don’t understand the past.”

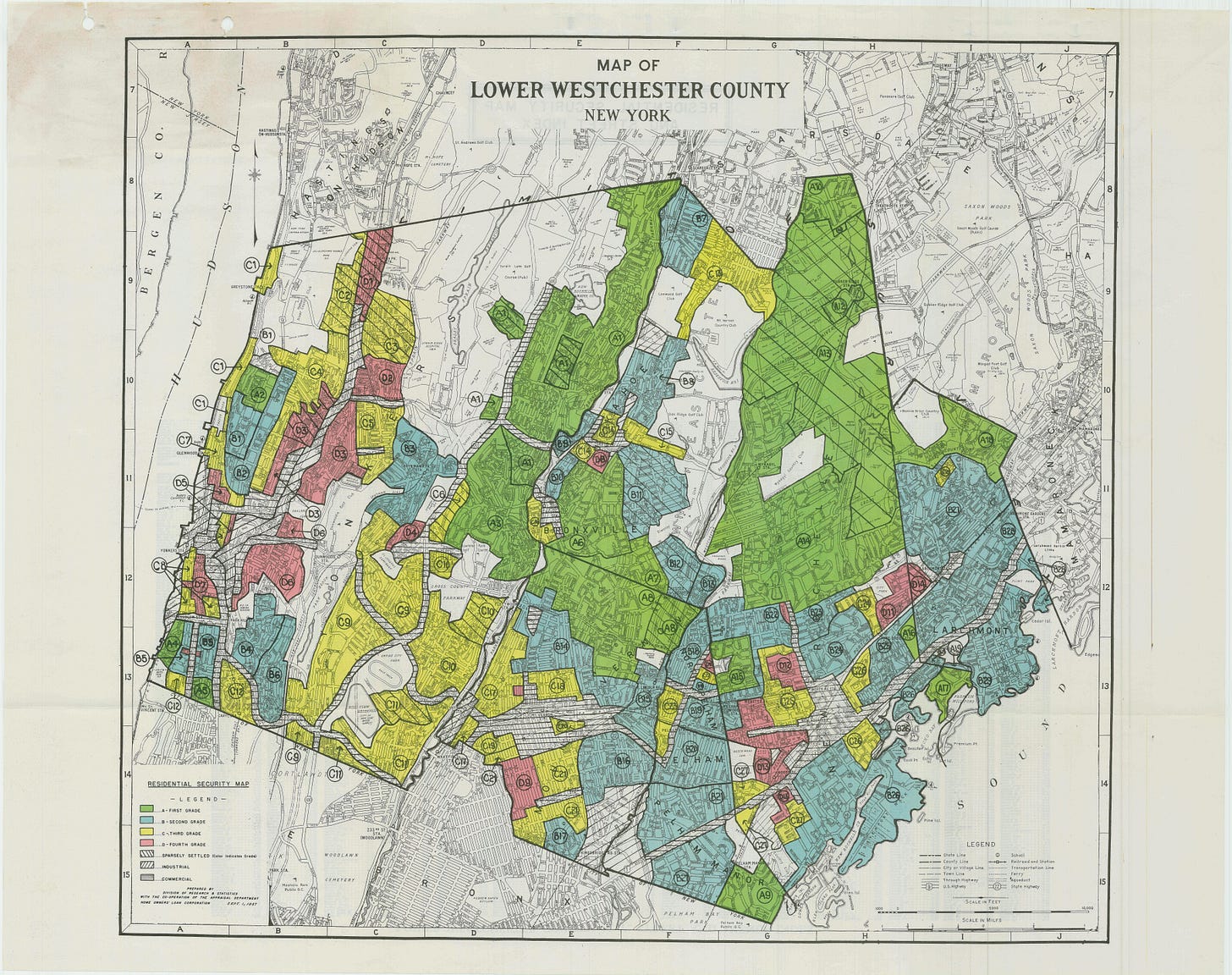

While Saturday’s panel was formally about housing discrimination in Chicago, those who know the history of the subject in Westchester County will be aware that this issue also hits very close to home. The county has a long history of housing discrimination, and was forced to sign a consent decree in 2009 requiring it to take serious action. Despite that agreement, New York State Attorney General Letitia James has recently filed high-profile actions against real estate brokers and others who have engaged in discrimination in Westchester.

With current debates about housing development in Croton, it would be naive to think that our village is immune from this kind of racism and discrimination. We can hope that our better natures will prevail against such prejudices, and be assured that anti-racism advocates will be vigilant against them.

Note: On May 19, what would have been Lorraine Hansberry’s 94th birthday, the Coalition will celebrate the anniversary at Bethel Chapel in Croton. You can find details here.

Note: While this article was provided free to all readers, local journalism needs your support. Please consider taking out a paid sub to The Croton Chronicle. It’s cheap! Only $5/month or $50/year, or $200 for a lifetime subscription. Click here for details:

To share this post, or to share the Chronicle, please click on these buttons:

Comments policy: Please be polite and respectful, no person attacks, no hate speech.