Indian Point Decommissioning -- Who's In Charge Here? (A Guest Editorial)

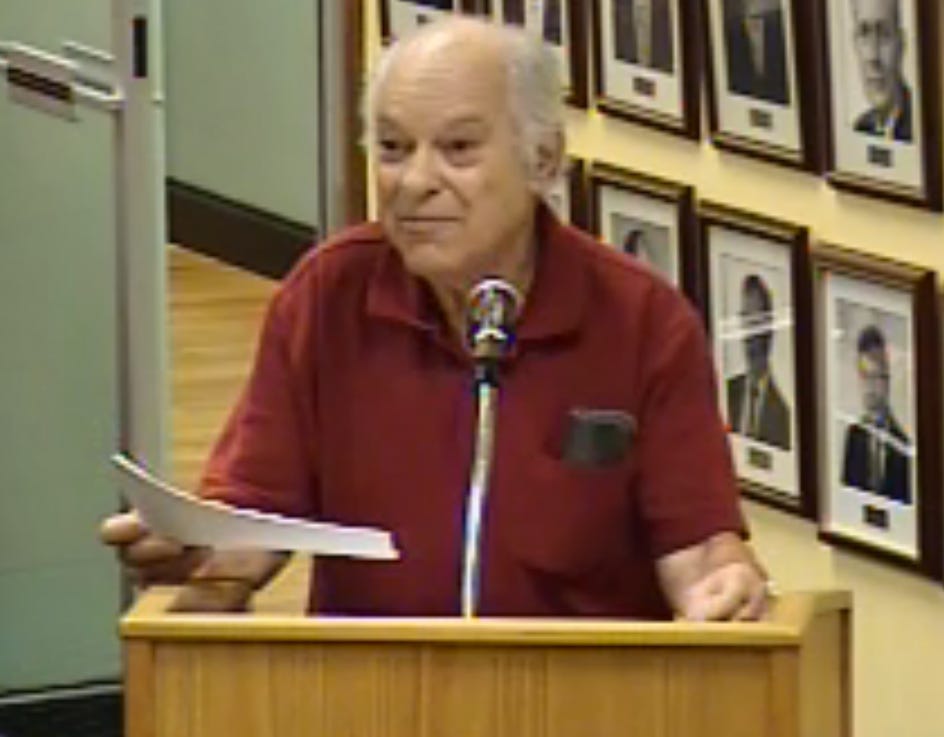

Croton resident and retired nuclear engineer Joel Gingold attended the first meeting of the Indian Point Decommissioning Oversight Board since Holtec sued New York state. Here are his thoughts.

By Joel Gingold

Note: With this post we inaugurate a new feature for The Croton Chronicle, the Guest Editorial. We will occasionally invite individuals who are knowledgeable and active in their fields to express opinions on timely issues of importance to Crotonites. If anyone has a suggestion for an editorial, either by themselves or someone else, please feel free to get in touch at TheCrotonChronicle@gmail.com

First, a little background to set the stage:

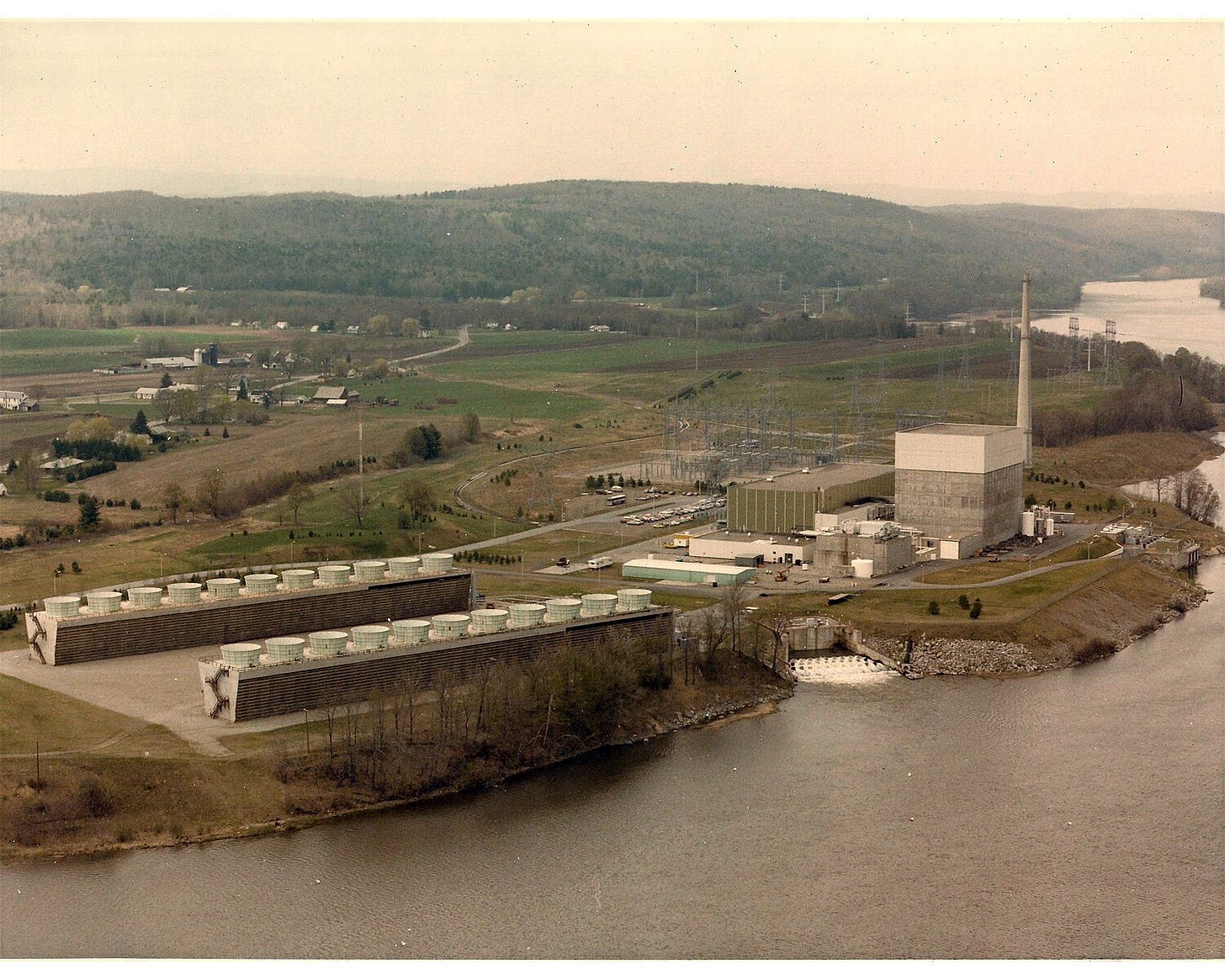

Holtec Decommissioning International (Holtec) is the current owner of the shuttered Indian Point Nuclear Plant and is responsible for its ultimate decommissioning. As part of that process, Holtec proposes to discharge about 1.3 million gallons of water containing the radioactive isotope tritium (and perhaps other radioisotopes) into the Hudson River. That water is currently in the spent fuel pools and other areas of the three shut down nuclear units on the Indian Point site.

In response, in August 2023, New York Governor Kathy Hochul signed into law the “Save the Hudson” Act, which specifically prohibits the release of any radioactive material from Indian Point into the Hudson. In April 2024, Holtec filed a lawsuit in federal court in New York contending that the law is unconstitutional, since the federal government had pre-empted the regulation of radioactive materials from the states and that Holtec’s proposed discharges were well within federal regulations. And here we sit today.

On April 25, 2024, a meeting of the Indian Point Decommissioning Oversight Board (DOB) was held at the Cortlandt Town Hall and the question of the proposed discharges figured significantly in the discussions held.

I should note at the outset that I am not a great fan of Holtec and would have much preferred to see NorthStar, which is decommissioning the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Plant, perform this task in Buchanan. However, we do not have that option. Similarly, I do not believe that the U. S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission is doing an adequate job of regulating decommissioning activities, including those of Holtec.

What Are Our Options?

The ultimate means of disposal of the tritiated water at Indian Point may well be decided by the courts in response to the lawsuit noted above. While I am certainly not a lawyer, it has always been my belief that the federal government has pre-empted the regulation of radiological discharges from the states. Thus Holtec is likely to prevail in such litigation, which, by its nature could even reach the U.S. Supreme Court. However, I am equally aware that trying to predict any court’s ruling is a fool’s errand, and the ultimate decision could well favor New York State.

Regardless of the final court determination, many years and much money will be expended by both sides in its pursuit, which will significantly delay the completion of the decommissioning process (Holtec has already stated that its inability to discharge the water will add eight years to the decommissioning schedule), unless New York State and Holtec can come to an agreement on a mutually acceptable alternative approach to the disposal of the tritiated water. I strongly believe that it is incumbent on both sides to energetically pursue this option.

I personally believe that Holtec can implement the discharges in accordance with the proposed plan, without any adverse impact on the Hudson River or on those of us who live along it. Discharges at significantly higher concentrations of tritium and other isotopes have been made at Indian Point—and hundreds of other nuclear plants around the globe, as well as at some medical and industrial facilities—for many decades without, to my knowledge, any confirmed negative impacts.

However, while I, myself, am not concerned over the releases, I am well aware that thousands of my neighbors, including many of our elected officials, are very troubled over possible physical and economic harm to the river and those who live along it. Thus, I would support an alternative approach to disposal of the offending liquid.

We currently have three such alternative approaches available to us:

· Evaporation of the water, which is a really bad idea for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that tritium released to the atmosphere as a result of evaporation is a significantly greater hazard than tritium in liquid form.

· Shipment of the water from the site, solidification, and burial in a licensed facility, as was done at Vermont Yankee. An excellent, comprehensive, and unbiased presentation of this option was made at the DOB meeting by Bridget Frymire of the New York Department of Public Service

· Storage of the water onsite for an indefinite period. This approach was championed by Arnie Gunderson, Chief Engineer of Fairewinds Energy Education, an anti-nuclear activist and speaker. Mr. Gunderson’s presentation was in response to a request to the DOB by a coalition of environmental organizations. He proposed that the water be stored in new tanks installed in the Indian Point turbine building for as long as needed, which would preclude that building from being removed from the site until after the ultimate disposal of the water.

Shipment, Solidification, and Burial

My own preferred alternative is shipment, solidification—either at Indian Point or at the disposal site—and burial of the solidified material along with all of the other radioactive components of the plant. This approach will permanently remove the material from the site so that it cannot ever impact the river and the inhabitants of our area. It will not add a great volume to the other plant components shipped to the disposal site, which will be transported and buried regardless of whichever approach is adopted for the tritiated water. It will bring relatively rapid, final closure to this issue, although it will necessitate additional costs. Such costs were estimated by Ms. Frymire as between $5 and $13 million. The decommissioning fund for Indian Point exceeds $2 billion.

The issue of “environmental justice” associated with the shipment and disposal of the water—are we simply transferring the problems of the tritiated water to the residents of the area to which it is shipped?—is a false one. All the other radioactive components of Indian Point will be shipped and buried in the licensed facility anyway, just as the radioactive components of all other decommissioned nuclear plants are similarly disposed of.

The question also arose as to whether there were any spills or any leakage of the tritiated water during transport from Vermont Yankee. While I am not aware of any, my own knowledge is far from complete. The NRC and/or Department of Transportation would certainly have records of such spills as they would have had to be reported, and more information might be available directly from Vermont Yankee as suggested below.

Onsite Storage

As became clear at the DOB meeting, there are many concerns over indefinite storage of the water at the plant, including time, costs, seismic events, tank overflow, leakage, the need to maintain some plant systems functional for an extended period, the need for staff for inspection and possible repair of storage tanks, etc. However, the most concerning aspect of onsite storage is that it is NOT a solution to the problem, only a delay in dealing with it. The ultimate “kicking the can down the road.”

As Mr. Gunderson clearly stated during his presentation, the storage would be for an indefinite period (“the storage duration is undefined and unspecified”) until we figure out what to do with it, whether it is the result of additional, yet uncommenced, scientific studies, new, yet unknown, technologies, or some another currently unknown solution. He noted that, “the ultimate disposal of water . . . should be a community decision to be made later. A decision should not be made until all of the scientific analyses regarding synergistic toxicity have been evaluated and precise, reliable information and data are available for analysis.” Thus, we will not know when we begin this alternative for how long such storage will last.

But perhaps we can try to place some bounds on this period. The half-life of tritium is somewhat over 12 years. If we use the standard argued by many that ten half-lives are necessary before a radionuclide becomes benign, that would mean storage for over 120 years. And even then, the tritium concentration, while drastically reduced, would not be zero. Storage for any lesser period would mean even higher levels of tritium and the hope that something will happen to facilitate its release. We would be facing a great unknown and basing the completion of the decommissioning on that (perhaps, vain) hope.

Onsite Storage at Vermont Yankee?

Beyond this, Mr. Gunderson’s presentation was misleading at best, and perhaps bordering on the disingenuous. He noted numerous times the “fact” that tritiated water was stored in the turbine building at Vermont Yankee—the implication being that this was Vermont Yankee’s solution to the problem. Yet, as was discussed by Ms. Frymire just a few minutes later, Vermont Yankee shipped all of the contaminated water off-site for disposal. She even displayed a photograph of the site that confirmed that the turbine building, in which Mr. Gunderson claimed the tritiated water was stored, had been completely removed from the site. Among the important facts completely absent from Mr. Gunderson’s presentation were:

· How much tritiated water was actually stored by Vermont Yankee in the turbine building?

· How long was such water stored there?

· Were new storage tanks constructed for storage of such water, and if so, what did they cost and what kind of surveillance and maintenance of them was necessary?

Mr. Gunderson also raised the issue of possible negative synergistic effects between the tritium and any PCBs in the Hudson River water. When asked if he had any scientific evidence of any such synergism, Mr. Gunderson stated that he did not.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Having listened to the presentations and the discussion of the water disposal issue, one point became immediately evident. There is much to be learned from Vermont Yankee with respect to the handling, storage, and shipment of the liquid, any problems encountered during the various steps, etc. etc. Thus, I would strongly recommend that the DOB contact its counterparts on the Vermont Yankee DOB and arrange a meeting, preferably on the Vermont Yankee site, to discuss all of these issues. Since Vermont Yankee is a couple of years ahead of Indian Point in its decommissioning, there may be many other facets of the process in which their input will prove valuable. Participation of NorthStar, the Vermont Yankee contractor, would certainly be beneficial.

With so much concern expressed over the disposition of tritiated water from Indian Point, one important factor seems to be completely ignored. What was done at other nuclear plants that underwent decommissioning? There have been over twenty such plants in the U.S. notably including:

Maine Yankee (ME) Connecticut Yankee (CT) Yankee, Rowe (MA)

Zion (IL) Duane Arnold (IA) LaCrosse (WI)

Big Rock Point (MI) Crystal River 3 (FL) Dresden 1 (IL)

Fort Calhoun (NE) Humboldt Bay (CA) Kewaunee (WI)

Millstone 1 (CT) San Onofre (CA) Rancho Seco (CA)

Pathfinder (SD) Trojan (OR) Oyster Creek (NJ)

And, if their water was discharged to an adjacent waterway, were there any adverse effects reported? It would seem that this is a critical factor in any ensuing discussions and it is incumbent on the DOB to ensure that this information is available to the board as well as the public.

Finally, as in so much of our public discourse these days, there is much heat generated amidst whatever light is shed on these critical issues. Consequently, as we proceed, we must be extremely careful not to fall into the trap of lauding and lionizing those who may tell us what we’d prefer to hear and denigrating and dismissing those whose message is different.

The tritiated water from Indian Point will ultimately have to go somewhere. Will its final disposition be decided by judges or by scientists and engineers directly involved in the decommissioning process, and how long will we have to wait for a resolution? Those questions will bedevil the process and the DOB unless and until concerted action is taken by Holtec and New York State to quickly resolve them.

Joel Gingold has been a resident of Croton for more than 80 years. He is a graduate nuclear engineer with degrees from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and New York University. A veteran of the U.S. Navy nuclear power program, Mr.Gingold spent a nearly sixty-year career as a consulting nuclear engineer to electric utilities and government agencies in North and South America, Eastern and Western Europe, and Asia. He also wrote two books about his life in Croton and elsewhere, “Now Hear This” and “On the Street Where I Live.”

Note: This Guest Editorial is free to all readers, but not all of our stories are or can be. To support local journalism, please consider taking out a paid subscription, at only $5/month or $50/year:

To share this post, or to share The Croton Chronicle, please click on these buttons:

Comments policy: Please be polite and respectful.

Has the option of barging the contaminated water out to sea and discharging it there been considered.

I just looked back at this article with Joel. He is so intelligent. We are fortunate to have him as a resident here. I wish he was on the board. Great article.