Chronicle Med/Sci: Health officials say the risk of humans getting avian flu is "low." How low is low and how do we know?

Human cases are rising, although most appear to be in people infected by birds, poultry, and dairy cattle. But the virus is getting ever closer to human-to-human transmission and a possible pandemic.

Editor’s Note: With this edition we introduce an occasional feature, “Chronicle Med/Sci.” It will focus on medical and scientific issues that do, or could, affect the people of Croton-on-Hudson in various ways. Among the journalistic hats the Chronicle’s editor has worn for nearly half a century is that of a science reporter, including 25 years as a correspondent for Science magazine (often reporting on infectious diseases) and a number of years teaching science journalism at NYU and Boston University.

Covid-19 was a traumatic event worldwide, and it is not over, even if the death rate has greatly diminished and the number of cases is much lower than at the height of the pandemic. Many thousands are now suffering from long Covid, which researchers have solidly established is a real thing and not a myth. Here in Croton, the pandemic brought division and trauma to our community, with bitter and still ongoing debates over whether mitigation measures—including masking and vaccination—were reasonable responses to a deadly plague, or an overreaction.

The pandemic broke out in the United States during the first Trump administration, continued into the Biden administration, and was highly politicized during its entire course. That politicization, on both sides of the political spectrum, made it more difficult to build consensus over what needed to be done.

We are now facing the possibility of a new pandemic, which, potentially, could be much more deadly than Covid-19. Public health officials, including at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), continue to tell the public that the risk of avian flu spreading in humans is “low.” But the CDC and other experts have also made clear that they are concerned about unambiguous evidence of rapid spread of the H5N1 virus (a leading cause of avian flu) and continue to remain on guard.

So what does “low” mean in this context? To understand that, it is necessary to hold seemingly contradictory thoughts in one’s head at the same time.

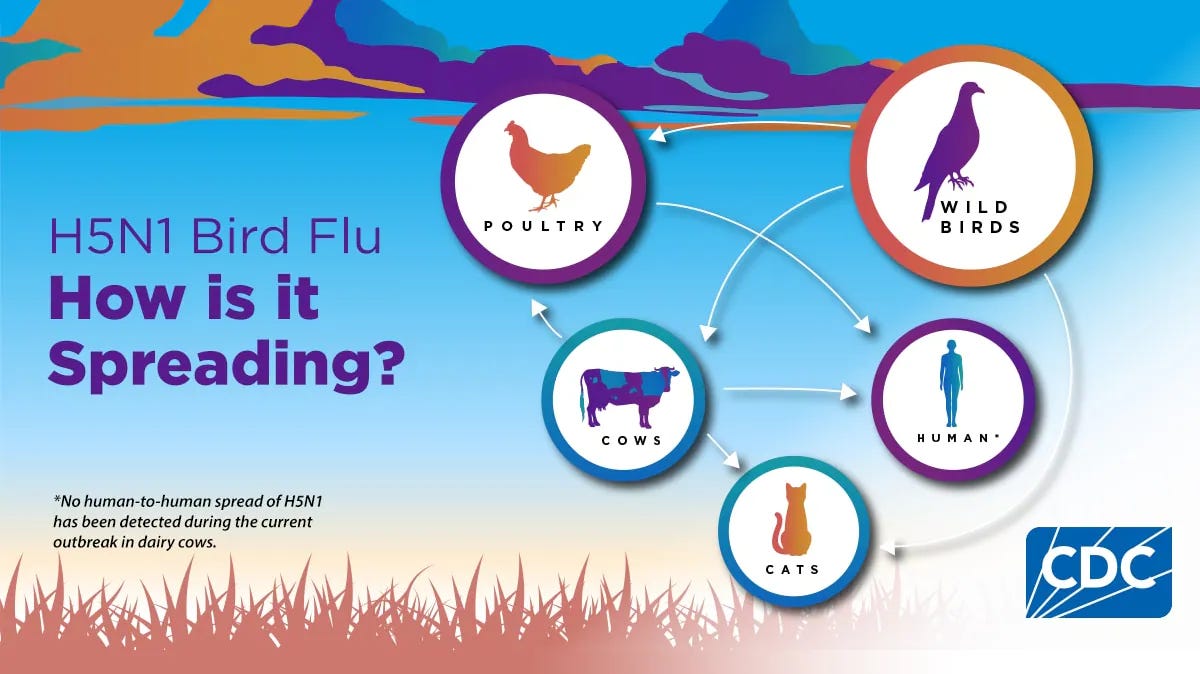

Right now, the risk appears to be “low” because there is no real evidence of spread between humans, although some people are contracting the disease through contact with birds, cows, and other animals.

On the other hand, there is plenty of evidence that the virus, in its evolutionary and genetic way, is trying as hard as it can to infect humans and spread amongst us. It is very close—just a mutation or two away—to being able to do so.

That is the scientific evidence that we will discuss in this column.

Avian flu, past and present

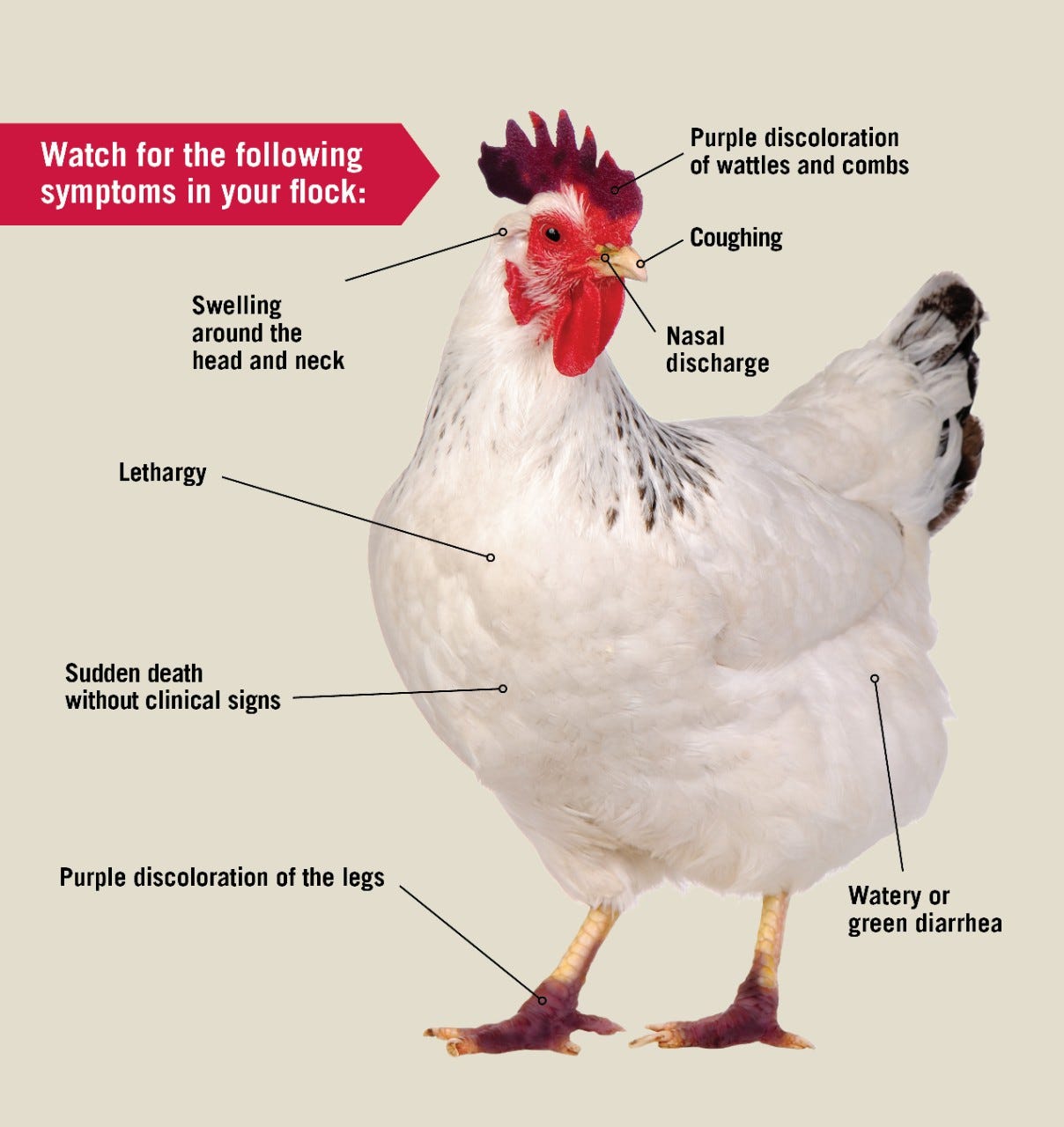

As readers can see from the timeline above, the H5N1 influenza virus, which causes avian flu, was first detected in domestic waterfowl in China in 1996. It went on to cause more than 860 human cases, mostly in Asia, with a 50% death rate. It was that extraordinarily high mortality rate that sent alarm bells throughout the community of public health experts and infectious disease scientists. The feeling at the time among researchers was that humanity had dodged a bullet, but for how long?

In 2003, another H5N1 outbreak began, starting again in Asia but spreading rapidly to Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. While there were few human cases this time around, the number of bird species affected increased, a sign that the virus was finding new hosts to infect.

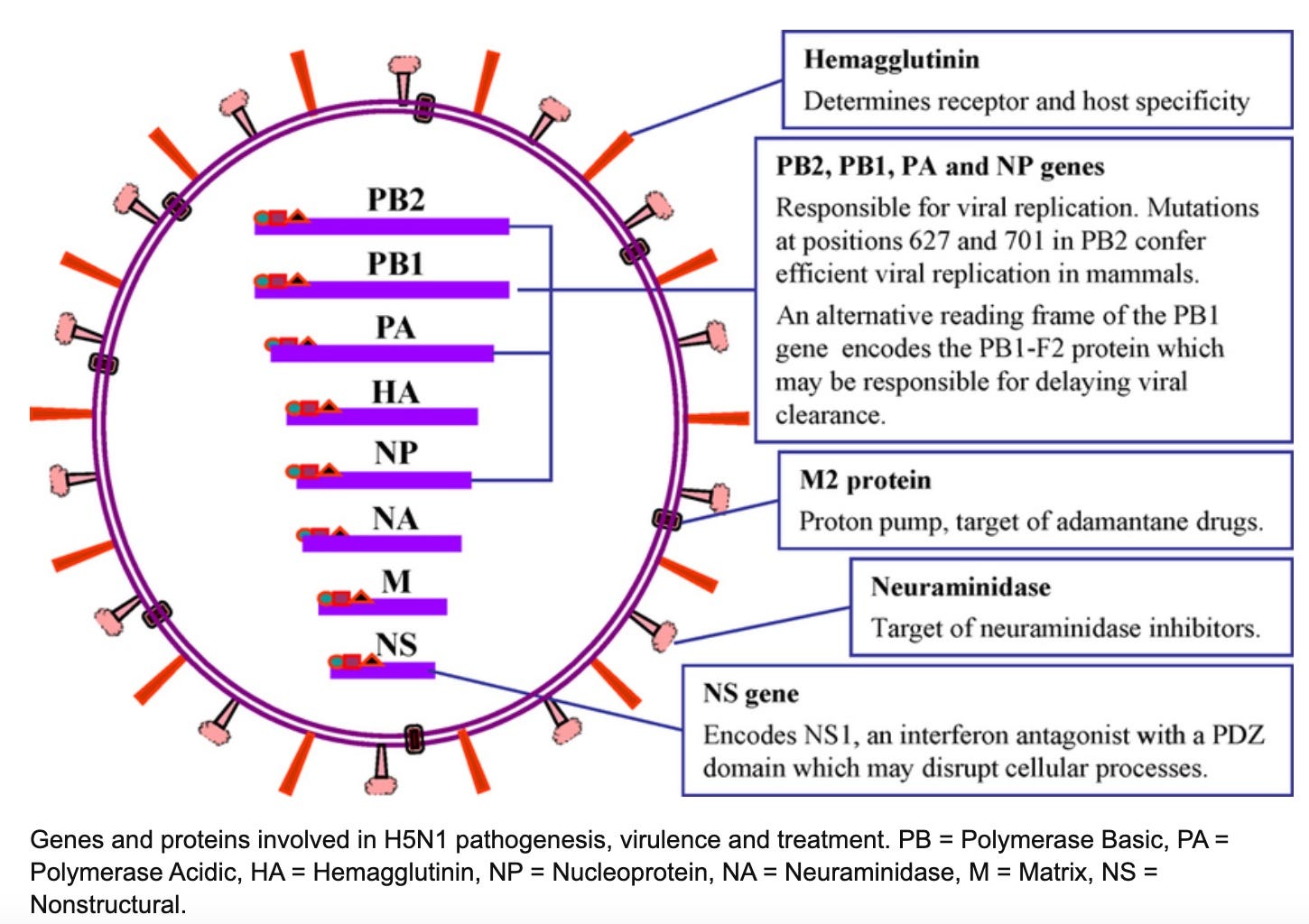

Beginning in 2014, the swapping of viral genes between poultry and wild birds led to new strains of the avian flu virus, such as H5N6 and H5N8. This so-called “gene swapping” is one of the main ways the virus can spread to new species. Avian flu has now spread to the United States. For a time, these new strains appeared to be dominant, and H5N1 seemed to be receding.

But in 2021, we entered the unprecedented and explosive animal pandemic phase we are currently experiencing. H5N1 has come roaring back, infecting hundreds of additional species of wild birds, spreading into dozens of mammalian species, and again producing human cases—and the beginning of new human deaths, even though in most victims the symptoms are fairly mild for now.

The spread of what is supposed to be a bird flu to so many mammalian species has been a real wake up call to virologists, epidemiologists, and public health officials, because that puts the virus one giant step closer to us humans.

As we said above, there is so far little to no evidence that the virus can spread between humans. But to more sober scientists, it is just a matter of simple genetics—and also, some think, just a matter of time.

H5N1’s genetic mutations: Just a receptor or two away from becoming a true human pathogen?

In November 2024, a 13 year old girl in British Columbia, Canada, was brought to an emergency department suffering from conjunctivitis in both eyes and a one day fever. She was discharged, but her symptoms got worse—this time including coughing, vomiting, and diarrhea—and returned to the emergency room, where she was diagnosed with respiratory distress and pneumonia, along with acute kidney damage. She had to be intubated and given oxygen and other therapies.

Genetic tests showed that she was infected with the H5N1 virus. Fortunately, she got better, recovered, and was discharged from the hospital after about three weeks. But the genetic analysis was very worrying to scientists: The girl was infected with a “genotype” of the virus called D1.1, which was most closely related to H5N1 viruses found in wild birds in British Columbia at that time. And when the researchers looked more closely at the genetic sequence of the virus, they found that it harbored mutations that helped it to bind more tightly to receptors in the human respiratory tract, called sialic acids, which the virus uses to gain entry into human tissues.

Then, in December, the CDC reported a severe case of H5N1 flu in Louisiana. Testing of viral samples from the patient, who was more than 65 years of age, showed that it also was from the D1.1 genotype, and it also had mutations that could help it more efficiently infect humans; one of those mutations was the same as that seen in the Canadian teenager. On January 6, the Louisiana patient died. It was the first H5N1-related human death in the United States.

A few days ago, the D1.1 genotype was detected in a Nevada dairy worker. Fortunately, so far at least, almost all of the several dozen human cases of avian flu now detected in the United States appear to have involved transmission between poultry or dairy cattle and humans, rather than between humans (last week, however, the CDC posted, then deleted, data showing avian flu spread between cats and people. The H5N1 virus, not surprisingly, had earlier been detected in raw cat food.)

Avian flu is here, in Westchester County.

Many or most readers will know from monitoring the news that avian flu is no longer something that is happening far away. The virus is suspected in the deaths of ducks and wild birds at the Queens and Bronx Zoos, Canada geese found dead at Carroll Park in Mount Pleasant tested positive for avian flu, and New York governor Kathy Hochul has ordered live bird markets to be closed in Westchester, New York City, as well as in Suffolk and Nassau counties, “Out of an abundance of caution and to thwart any further transmission,” she said last Friday.

So what does all this mean for us in Croton? Does it mean we should all mask up, stop eating chicken or drinking milk, and give away our cats?

No, although with Covid-19 still very much alive and among us, villagers who are going around with masks in public should not be the subject of ridicule (or worse, laws against masking.) There is no reason for panic—yet.

On the other hand, if H5N1 (or other avian flu viruses, such as H5N9, which has just made an appearance at a duck farm in California) crosses that final genetic barrier into being an effective—and possibly deadly—human pathogen transmitted from person to person, we could be in a lot of trouble. So we need to watch out, make sure we are well informed, and be prepared to take pretty serious measures.

This time around, we must hope that our response is driven by science, not by politics, as difficult as that might be for a small community like ours. The avian flu virus does not care what your politics are. From an evolutionary perspective, it is doing its best to mutate so it can dock onto your sialic acid receptors, get into your lungs, multiply into millions or billions of viral particles, and then infect someone else.

There are things we can do to prevent that from happening; being well informed is certainly one of them. But time may not be on our side.

************************************************************************************************************

To share this post, or to share The Croton Chronicle, please click on these links.

I hope we all learned our lessons on how badly Covid was handled. Both political parties succumbed to the pressure to use it to their own advantage. Millions paid with their life, millions more are living with long term side effects, whether it’s their health or their inability to read at grade level. Both parties eroded trust in science and expertise. With the current hyper partisan climate, I do not have a whole lot of faith we’ll do better this time around.

Thank you for your reporting and raising the awareness Michael. We do not have to be divided along political lines for something like this.

Thank you for your very informative article. I believe it is unfortunate that routine testing of those individuals in occupations at risk are not being availed of testing for the presence of avian flu, and or provided with the opportunity to be vaccinated for free from the current government stockpiles available to protect them. We should be pushing forward as expeditiously as possible to develop safe and effective commercially produced vaccinations for avian flu that is routinely made available to workers who are occupationally exposed. We routinely avail healthcare workers with a prophylactic regiment for years in the event of a significant exposure to a contaminated needle from an individual who has HIV. Why do we seem to be going backwards? My suspicion that it is in part caused by the politicalization of our government in every facet of our life with the aid of the fourth estate.